My thoughts on ‘Our Israeli Diary, 1978’ by Antonia Fraser

Book Review: Joely Spevick shares her insights on Antonia Fraser’s ‘Our Israeli Diary, 1978’.

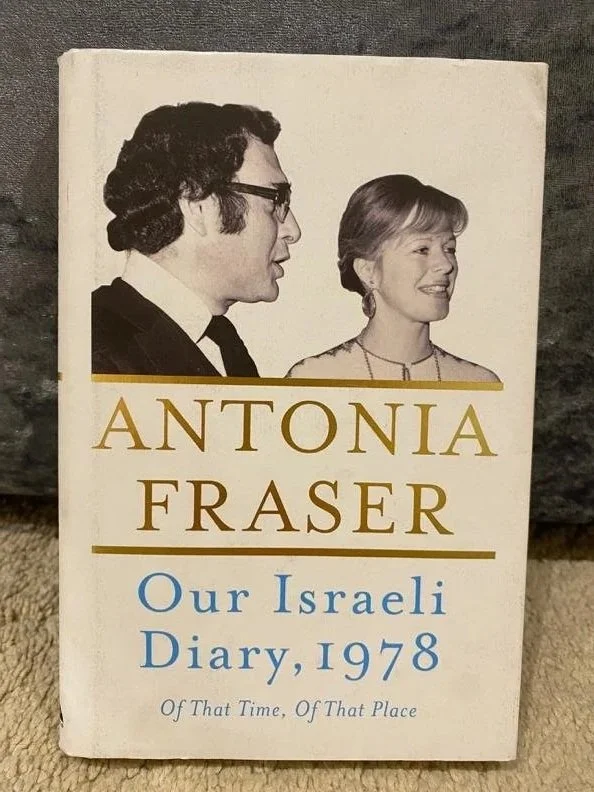

I had never heard of Our Israeli Diary, 1978, nor of Antonia Fraser, until about a month ago, when I went to a book warehouse called 66 Books with a friend (if you like cheap books, I highly recommend visiting!). Antonia Fraser, now 93 years old, is a British author and historian, as well as the widow of Harold Pinter, a renowned British dramatist and the 2005 Nobel Laureate for Literature. She is Catholic; he was Jewish. In 1978, the couple visited Israel at the time of Israel’s 30th Anniversary of Independence. Our Israeli Diary, 1978, is Antonia’s personal diary from their two-week trip.

The diary was only published decades after the trip in 2016, when Antonia rediscovered it in a cupboard. Whilst she did authorise its publication, it feels somewhat wrong to review or judge someone’s personal diary, since it was not intentionally written for public viewing. This piece, therefore, serves as a structured outlet for my reflections and thoughts. I also wanted to bring this book to people’s attention because I think it’s a niche and highly unique piece of writing.

Something I learnt:

Antonia notes that a ‘prominent Jew’ and ‘hero’ called Teddy Sieff is on the same flight out to Israel as them. After some research, I discovered that Teddy Sieff’s real name is Joseph Sieff. He was President of M&S from 1967 to 1972 as well as the vice-president of the British Zionist Federation from 1961 to 1965 (now the Zionist Federation of Great Britain and Ireland). Fraser calls him a hero because he survived an assassination attempt in 1973 by a terrorist whose real name is Ilich Ramirez Sanchez, but he was known as Carlos the Jackal. Carlos went to Sieff’s home in St. John’s Wood, ordered the maid to take him to Sieff, where he shot at Joseph Sieff in the bathroom but was unsuccessful in killing him. Carlos the Jackal fled, but this was apparently his first assassination attempt of his career that would span 20 years. He worked on behalf of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, which was founded in 1967, is the second largest faction of the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) and is a proscribed terrorist group.

Something I found funny:

The room Antonia and Harold stay in during their visit has a Hebrew letter on the outside, which Antonia describes as looking like a ‘sideways dustbin’. (I’m still not entirely sure which letter she is referring to — if anyone has any idea, please enlighten me!)

(Antonia and Harold stayed in a place called Mishkenot Sha’ananim, the first community to be established outside the Old City of Jerusalem. This community was founded in 1860 by Sir Moses Montefiore, a British financier and banker.)

A picture of Mishkenot Sha’ananim. The windmill is named Montefiore Windmill, built by Sir Moses Montefiore to provide the community with a way to mill their own flour.

Something I found surprising:

There were a couple of things. Firstly, the amount of books Antonia reads is ridiculously impressive. Before the trip she reads ‘Saul Bellow’s book about Israel’ (which to my knowledge could be To Jerusalem and Back), but whilst on the trip she reads:

Abba Eban’s autobiography (fun fact: Abba Eban was the first ever editor of the Young Zionist in the 1930’s! He was Israel’s Foreign Minister from 1966-1974)

Story of My Life by Moshe Dayan (who was the Defence Minister during the Six Day War)

O’ Jerusalem! by Larry Collins (a historical book detailing the 1948 Arab-Israeli War and the battle for Jerusalem)

The Dead Sea Scrolls by Edmund Wilson

Of course, Antonia Fraser is an author and a historian – a significant part of her job is to read. Nevertheless, I think I can confidently posit that this is an objectively mind-boggling amount of information to consume over 14 days, but really, it’s incredibly admirable and we should all be taking a leaf out of her book (pun intended?) in the way she strives to educate herself on such a highly complex and nuanced subject.

The second thing that wasn’t necessarily surprising, but something I didn’t anticipate (because I didn’t know that she is Catholic), Antonia takes a much bigger interest in the Christian side of Israel’s history than I, admittedly, usually do (although I did visit Nazareth when I was on Year Course in 2021 – see the picture!). Not only was it refreshing to hear about the Christian sites and landmarks, but it was also refreshing to see Israel being explored through the eyes of a non-Jewish person, something I at least rarely come across. I really appreciated this perspective.

My biggest takeaway:

In all honesty, and it sounds rather bleak, but something that kept striking me as I was reading was that history really does repeat itself. Despite coming across this book nearly 50 years after it was first written, there were uncanny and quite unsettling similarities between Israel’s political sphere in 1978 (or the 1970s in general) and that of the current one of Israel. There were three points in the book where I felt this the most:

1. Antonia states in response to Moshe Dayan’s book: ‘As if the world had decided that really unique among states, Israel must be a moral state… something no other state is expected to be!’ (p27)

2. She states of Menachem Begin, the then-Prime Minister: ‘The point is he is their Prime Minister and he is doing great harm to the Israeli image — at the same time as a new generation arises to whom the Palestinian refugees, not the victims of the Holocaust, are the underdogs.’ (p54)

3. On 20th May, they hear news of an unsuccessful terrorist attack on El Al passengers in Orly Airport in Paris. They are ‘relieved to hear’ that the terrorists have been shot dead, and one of their friends’ reactions reminds Antonia of Harold’s reactions to the news of the Raid of Entebbe (a 1976 hostage rescue mission conducted by the Israeli military after a civilian passenger flight was hijacked by terrorists between Tel Aviv and France).

I sadly feel like these examples don’t require any further explanation as to why I drew comparisons between Israel then and Israel now. Although it does dawn on me whilst writing this that perhaps this isn’t so much a case of history repeating itself, but more a case of not a lot fundamentally changing in 50 years? Or perhaps if it has changed, it has changed for the worse? Perhaps that’s a conversation for a different article. In any case, let’s hope that 50 years from now the Israeli politics of 1978 does not hit so close to home.

On a more positive note, I found a similarity that was rather heartwarming, and this is regarding how the visit to Israel strengthens Harold’s Jewish identity. Interestingly, Antonia reveals that Harold had avoided visiting Israel before because he ‘feared to dislike the place, the people’, which to me suggests that Israel had been put on a pedestal to Harold. A land so disputed and contested must be something extraordinary, and to visit Israel invites this image to shatter and be falsified, yet Harold finds that he is ‘very happy at both the place and above all the intelligence we find’, emphasising how it is truly the people of Israel that make it the extraordinary place it is. He likes it so much so that he talks of his next visit to Israel, merely five days into the trip, which made me laugh because since the conclusion of my Year Course in 2022, I have not visited Israel without planning when my next trip will be. Moreover, Harold tells Antonia regarding their trip: ‘I definitely am Jewish. I know that now.’ Harold was 48 years old in 1978; it was only after a visit to Israel halfway through his life that he felt certain of his Jewish identity. I believe this illustrates the significance of history and how crucial it is for us to understand our origins before we can comprehend who we are today. I believe this moment will resonate with many people.

For me, this is one of the most powerful moments in the diary, and Antonia’s response is just as interesting. She says she could ‘live here in every way except one, and that’s not being Jewish.’ She says she ‘would never be a part of it in the most real way.’ My instinct is to rebut this, to point to the diverse melting pot that is Israeli society and say, ‘Look how many people call this country home!’. On the other hand, I am Jewish, so I could never properly argue with her remark because I will always feel like I have a place within Israel.

I highly recommend picking this up if anything I’ve said has even remotely piqued your interest. It is a tiny little book which practically bursts with history and personality, much like Israel itself, and this book has renewed my appreciation for the stories behind the land. To leave you with one of my favourite quotes, before their initial flight, Antonia recounts that she and Harold both bought new shoes from M&S for the trip because she says: ‘I think we both believe we shall tramp through a great deal of history’.